This is the final piece of a three-part series surveying the history of workers’ compensation. Prior to 1911, an individual residing in the United States, regardless of their state residency, who suffered a workplace injury could only recover damages by utilizing traditional tort based law. In other words, an injured worker would need to sue their employer and claim the employer’s negligence or intentional conduct caused the subsequent injury. The employer could raise defenses such as contributory negligence or assumption of risk to bar the receipt of monetary damages. This system was often cumbersome, time-consuming, unpredictable, and expensive for both the employer and employee.

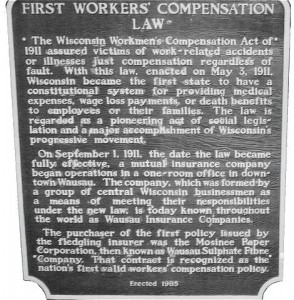

In 1911, the State of Wisconsin passed the first statutory law specifically addressing workers’ compensation entitlement benefits. The goal of the act was to create an efficient system to adjudicate claims while reducing legal hurdles for the injured worker thus creating a predictable system where the employer could foresee limited monetary risks. The Wisconsin system created a “no-fault” legal system in which the injured worker would no longer need to prove that the employer engaged in some type of culpable negligent or intentional conduct. According to the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development, “the intent of the law was to require an employer to promptly and accurately compensate a worker for any injury suffered on the job, regardless of the existence of any fault or whose it might be.” The legislation provided for wage loss benefits, cost of medical treatment, disability payments, and payment for vocational rehabilitation training.

The legislation also eliminated an injured workers’ right to seek damages historically available through the tort system. As discussed in part two of the series, by 1911 the general public had become more concerned about the deplorable and often unsafe working conditions in factories across the nation. The Wisconsin Workers’ Compensation Act barred the injured worker from pursuing non-economic damages awarded by juries, including pain and suffering and loss and enjoyment of life. Similar to today’s ubiquitous state-based worker’s compensation acts, the Wisconsin Act enumerated the specific type of damages an injured worker could receive, thereby duly preventing the injured worker from requesting a jury to adjudicate damages. The judge adjudicating workers’ compensation claims, as a finder of fact, could not award benefits beyond the provided benefits in each respective act. The Wisconsin Act, while providing for specific benefits and shifting liability to the employer under the no-fault system, also provided employer’s with protection by limiting the scope of damages and removing the question of damages from unpredictable juries.

In the decade following the Wisconsin Act, nearly every state in the union promulgated some form of a workers’ compensation act. Mississippi was the last state to pass an act, but did so by 1948. Interestingly, as Gregory Guyton points out in his “Brief History of Workers’ Compensation,” the medical profession did not receive the worker’s compensation system with open arms. Medical professionals generally viewed worker’s compensation as a form of socialized medicine. According to Guyton, when the Social Security disability insurance act was created in the 1930s, disability based medicine expanded becoming lucrative for medical professionals. On the heels of the respective disability acts, the American Medical Association published the first guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment in order to develop a method to provide compensation evaluations. In Colorado, the legislature has decided to continue using the third edition of the AMA Guides to permanent impairment. The guide is currently available in six editions.

Given the volume of claims in any one state for benefits, each state may elect to create administrative agencies to adjudicate workers’ compensation claims. Colorado, for example created the Office of Administrative Courts in 1976 to hear an array of limited subject matter cases, including workers’ compensation. Prior to that time, the District Court handled worker’s compensation claims. Any individual working in workers’ compensation is familiar with the respective administrative system and ministering the claims. As the American workforce changes in age, and disability laws, including the ADA, become more pervasive in the work environment, there are open questions as to whether disability acts or managed health care administered by the federal government will substitute various aspects of workers’ compensation. For now, the workers’ compensation model most are familiar with will remain stable, subject to changes made by each respective legislation.